Article by Jasmien for Fashion United: Why everyone is talking about circular economy as the solution?

On ‘Sustainability Clarified’ – a series of Jasmien Wynants for Fashion United.

In this series, we take you into the wonderful world of environmental science. Each article clarifies a key topic related to ‘sustainability’. We zoom out to the bigger picture and then look in more detail at how these complex concepts are linked to the fashion industry.

This time, we talk about… the circular economy.

April 14, 2023, Fashion United

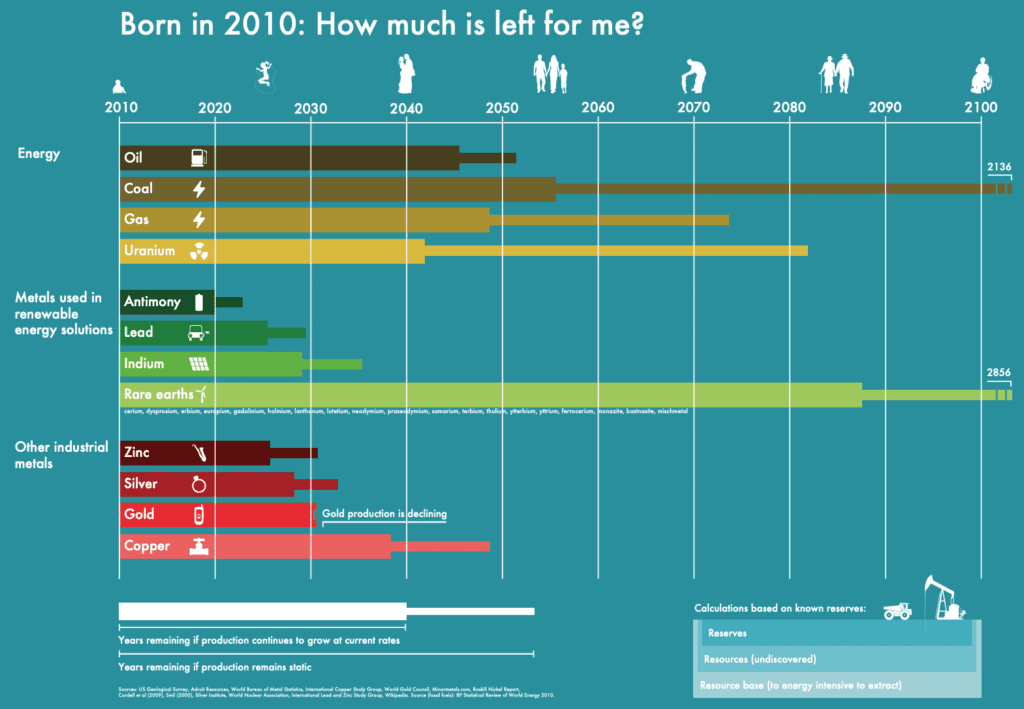

A system under pressure: are there limits to growth?

We don’t really dwell on it, but we live within an economic system every day. A system that changed over the years. Our thinking and actions, here in industrialised countries, are founded on an idea of ‘unlimited economic growth’. Since the end of World War II, consumption has been increasing. We strive for annual economic growth in the form of ever-increasing wealth. But is such perpetual growth realistic?

In nature, nothing grows forever. The means and resources needed to do so are simply not endless. The smallest bacteria to the largest trees have a certain maximum size and at some point reach a ceiling in their growth. That we often assume infinite growth in our economy, with businesses and economies striving for continuous increases in profits and productivity, is contrary to the limitations of our planet. We already see many consequences linked to this today: resource depletion and environmental damage.

From linear to circular

So a sustainable economy should strive to balance economic growth with preserving the natural systems and resources needed for our prosperity. Hello, circular economy!

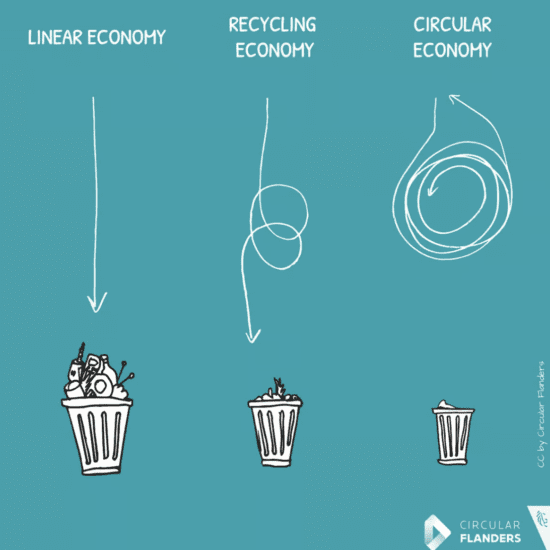

We often think of ‘circular economy’ as recycling, but it is much more than that.

The simplest way to explain circular economy is to compare it to the system we know today: the linear economy. That system is based on the ‘take – make – waste’ principle. We take new raw materials (like cotton), we use them to make a garment (like a T-shirt), we sell it to the consumer, who wears it and throws it away again.

The circular economy goes against this and focuses on longevity of products in the first place. The central question here is: how can we use as few new raw materials as possible, use them as efficiently as possible and keep them in the loop for as long as possible? So how do we ensure that we don’t actually create any waste at all?

Goodbye ‘planned obsolescence’, welcome ‘right to repair’

Just a step back in history. The concept of ‘planned obsolescence’ emerged in the 1920s. Manufacturers were experimenting with ways to limit the lifespan of products to stimulate demand for new products.

One of the first examples was a cartel of lamp manufacturers formed in 1924 to agree on the production and sale of light bulbs with a limited lifespan. Later, this strategy was also applied to electronics, household appliances, cars, smartphones and also clothing.

You will recognise the two forms of planned obsolescence in the fashion industry:

1. Technical obsolescence: a product is made so that it breaks down or wears out quickly (or also: low-quality clothing that tears, pills or loses colour after only a few washes).

2. Stylistic obsolescence: a product is made so that we want to replace it quickly because the style is outdated (or also: ever-new trends, ever more collections and seasons, fast fashion and ultra fast fashion).

Although this concept has been around for many decades, in recent years there has been an increasing focus on its negative impact on the environment and society. There is therefore a growing demand for sustainable and circular products, which are designed to last and are easy to repair and recycle.

The call is also growing stronger from Europe. There, we are looking at a ‘right to repair’ – the right we have as consumers to buy quality items that we can repair. Moreover, the Union’s strategy for sustainable and circular textiles has an important goal in favour of the circular economy: ‘make fast fashion out of fashion’. It even launched an entire RESet the Trend campaign around that.

So what about a circular fashion system?

As you can guess, it’s not easy. To change an entire system requires a transition from one system to another. It is complex but undoubtedly requires efforts from various actors.

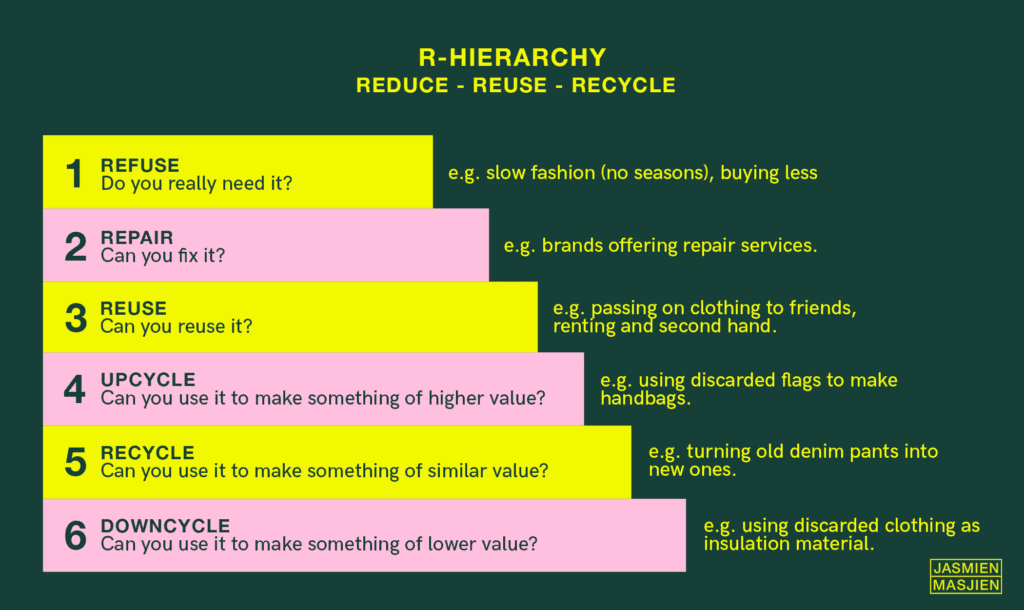

Fashion companies must dare to question the current business model. This can be done, for instance, by setting up rental or partial systems or designing quality pieces across seasons (slow fashion). It also looks at closing cycles: can clothes be collected and reused? How can clothes be made to last and be easily recycled in the end? And that without harmful effects on people and the environment?

Consumers also have a role to play because while something may be made to last, shoppers should of course take care of it and not get tired of it too quickly. Between 2000 and 2014, global clothing production doubled (MckKinsey). We are buying more clothes than ever and also throwing them away at an ever-increasing rate. This problem of overproduction and overconsumption is not sustainable. Therefore, it is important to think carefully with every purchase whether you need it and will wear it long enough.

One of the best reminders both for businesses and consumers is the ‘R hierarchy’ that can guide you in making decisions.

And then, of course, the key question arises: will all the world’s problems then be solved?

A transition of an entire system does not happen overnight. We sense a system that is faltering and see increasing pressure also from Europe and upcoming legislation gives hope.

However, the fashion industry plays in a global and complex chain with all its challenges. We export and dump a mountain of textiles in Africa and Asia every year. According to EEA. the amount of used textiles we export from the EU tripled in the past 20 years.

In addition, we have also seen great economic success in recent decades with large (ultra) fast fashion players conquering the internet with clothes sold at dumping prices, at unseen speeds and in huge quantities. The most vulnerable in the chain: garment workers in the Far East and low-wage countries still pay the price here.

A circular system is complex but conceivable. It can be part of the solution, as long as we do not lose sight of the international character, the social aspect and the focus on ‘degrowth’ (aiming for a stable level of production and consumption in balance with the planet’s limits).

We asked the scientist… Veerle Vermeyen, PHD candidate circular economy for clothing at KU leuven

“In the previous articles in this series, it has already been mentioned several times that bringing less new clothing to market is one of the most impactful actions to achieve a sustainable fashion system. Doing more with less is central to the circular economy. This can be done by using clothing that is already in circulation as intensively as possible. After all, we then avoid spending unnecessary resources on the production of new clothing and the processing of discarded clothing. So don’t be too easily seduced by messages from companies encouraging more consumption under the slogan of ‘sustainable production’.”

“The benefit of more intensive use may become clearer by thinking about the ‘impact per use’: the more often a garment is worn, the smaller the relative impact of production, transport and waste disposal become in the total life cycle of the garment. For example, the total impact of production and waste disposal of 15 T-shirts worn twice each is much greater than the impact of one T-shirt worn 30 times. More intensive use can be achieved on the one hand by a shift towards ‘slow fashion’, where consumers consciously choose quality and timeless clothing with the intention of wearing it for a long time. On the other hand, there is still room for the necessary variation in outfits through greater use of rental clothing or second-hand channels, where different users together ensure that a garment is actively worn.”

“However, clothing will always age through use and thus be discarded, so new clothing will also always be needed. Here, it is important to think about the use and discard phase already during the design phase, as this will greatly determine the extent to which repair and recycling are possible. For instance, garment-to-garment recycling (a cycle where the materials in discarded garments serve as input for new garments) is currently practically impossible due to the complex mix of materials and chemicals used. Europe wants to address this in the coming years by using new regulations to break down the current barriers to garment-to-garment recycling and thus start closing the cycle.”